There’s a film you may have heard of called A Cock and Bull Story, starring Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon. The film is based on the 18th century novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy. The novel itself is about Tristram’s attempts to write his life story. One of the central jokes of the book, however, is that he cannot explain anything simply. Instead, he must make explanatory diversions to add context and colour to his tale, to the extent that his own birth is not even reached until Volume III. To give you an idea, this is the very first sentence in the book…

I wish either my father or my mother, or indeed both of them, as they were in duty both equally bound to it, had minded what they were about when they begot me; had they duly consider’d how much depended upon what they were then doing;—that not only the production of a rational Being was concerned in it, but that possibly the happy formation and temperature of his body, perhaps his genius and the very cast of his mind;—and, for aught they knew to the contrary, even the fortunes of his whole house might take their turn from the humours and dispositions which were then uppermost;—Had they duly weighed and considered all this, and proceeded accordingly,—I am verily persuaded I should have made a quite different figure in the world, from that in which the reader is likely to see me.

Because of all of this, Tristram Shandy is considered to be an early example of postmodernist literature and many believe it to be an unfilmable book. Obviously, this didn’t stop the makers of A Cock and Bull Story. They got around this by making a film about people trying and failing to make a film about the novel, much how Tristram tries and fails to tell his life story. It’s clever and funny stuff.

I bring this up as this is how writing this blog post has felt to me. For ages, I’ve been saying I would write something about John Money and the history of the term gender identity and how trans and intersex became so intertwined in medical literature. The problem is, it’s almost an unrecordable history. Much like the makers of A Cock and Bull Story, the texts I must go from are filled with spurious claims and unnecessary diversions. The language is deliberately vague, while promising details, with its verbosity, that are not there. Many of the former writers and researchers, especially Money himself, were more concerned with self-aggrandising than writing anything that might be useful or clear to others. It’s frustrating. That being said, I think it’s an important story to tell, so I’m going to try. I can’t promise it will be clever and funny, like the film. I can’t even say it will be a definitive history, and I feel like it may take more than one post to write it all, but let’s have a go. Here is my gender identity homage to A Cock and Bull Story…

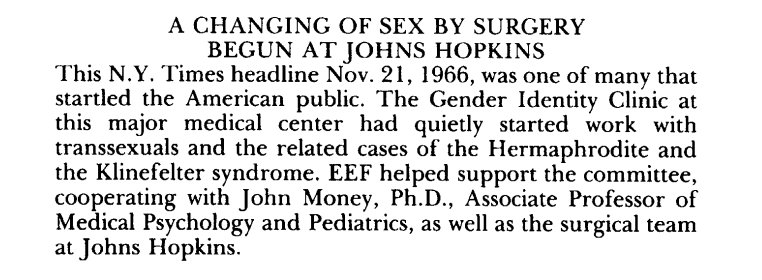

The term gender identity did not appear in our lexicon until some time in the 1960s. First usage is contested, which gives you an idea of why this history is problematic from the get-go. The OED originally attributed it to the Spring 1969 issue of the Erickson Educational Foundation (EEF) Newsletter, Vol. 2, however, this is contested by John Money himself, who states that the term was actually used in volume 1 of EEF, in this passage…

This press release is referencing the opening of the ill-fated (we’ll get onto that another day) gender identity clinic at John Hopkins Hospital, previously known as the sex-change clinic. Obviously, this phrase didn’t spring up from nowhere, so we’re going to begin by looking back to understand how it came into being.

Now, gender and queer theorists will tell you that “trans people have always existed” but this is a problem, as we cannot attribute modern theories and beliefs about gender to people who lived in an entirely different time. Many examples that queer theorists cling to seem to be women who wished to escape the historical confines of being a woman, such as the case of James Barry, which some of you will be familiar with due to a controversy earlier this year regarding a book about Barry’s life. For those of you that don’t know, Barry was born Margaret Anne Bulkley, some time between 1789 and 1805. The child, Margaret, was educated with a view to maybe becoming a tutor, but when she failed to find employment, her family, some close friends and herself hit on a plan. She would disguise herself as a man and attend medical college. This plan was successful. Margaret attended the University of Edinburgh, disguised as a man with the new name James Barry, and successfully qualified as a surgeon in 1813. She went on to have a glittering career (one of the things she is noted for is completing the first ever successful caesarean section), continuing in her guise as Barry. She eventually died in 1865 and only then did the public become aware that Barry was female. It’s impossible to know if, had Barry lived now, at a time when women can attend universities and train to be doctors, she would have chosen to live as a man. It seems odd to suggest she definitely would have done, when the sole purpose of the deception was to gain entrance to medical school. It’s also impossible to say whether Barry ever expressed any thoughts about her own identity. For this reason, I am going to discount the histories of GNC people, co-opted by queer theory, and jump into the science literature instead. This brings us into the 19th century.

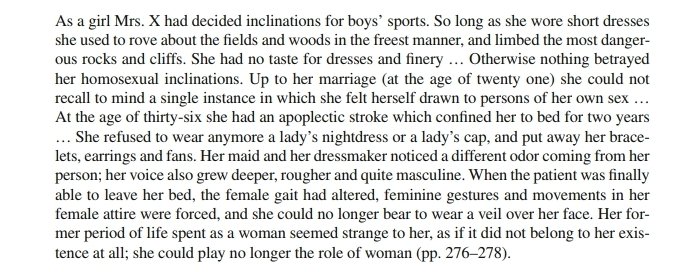

One of the earliest references I have found about people who felt an incongruence with their sex and their inner experience of their sex (gender was yet to work its way into science and medical literature) is in the work of German psychiatrist Carl Friedrich Otto Westphal. He named the syndrome Kontrdre SexualEmpfindung (contrary sexual self-awareness – coined in a book of the same name which was published in 1870). However, it’s important to note, that as one or two of his cases were not clearly transsexuals (by modern standards), this term was overextended by others to include homosexuality. This is typical of other work at the time. Another example is the book Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), by Austro-German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing, which documented the histories of people who expressed a strong desire to live as the opposite sex as well as people who had been born one sex but were living as another. One such example can be seen here…

This conflation of trans and homosexuality, really, comes as no surprise in its historical context. Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, a German lawyer, journalist, and author (btw, I have no idea why everyone is German at this point in the story – any suggestions for theories about this would be gratefully received), who is regarded as a pioneer of the modern gay rights movement, had invented a third sex theory, in the 1860s. He had proposed that men’s spirits in women’s bodies (urningen) and women’s spirits in male bodies (urnings) were the “cause” of homosexuality. This theory gained in some popularity and was considered very progressive for its time, although it was later abandoned. However, it’s easy to see links with Ulrich’s theory and the modern transgender movement, which seems to rely, in many cases, on a belief of a gendered soul of some description.

This conflation of trans and homosexuality (I should probably point out that neither of these terms existed yet) continued until the work of Magnus Hirschfield in the 1920s. Hirschfield is credited as being the first person to distinguish between homosexuality (the desire to have partners of the same sex) and transsexualism (the desire to live as the other sex). What Hirschfield wanted to show was that cross-dressing (transvestitism) was not identical to homosexuality. He argued that there were four main types of transvestites: heterosexual, homosexual, automonosexual (or narcissistic), and bisexual. It’s worth noting that many of Hirschfield’s subjects would not be considered transvestites in the modern sense of the word but would be more accurately described as transsexuals. To be clear here, and I know the language is considered outdated by many, but it’s what we have to work with – a transvestite is someone who dresses as the opposite sex, a transsexual is someone who undergoes some medical intervention in order for their body to appear as the opposite sex.

Hirschfield’s work was then built on by Henry Havelock Ellis, an English physician and writer. Ellis disagreed with Hirschfield’s terminology and instead shifted the emphasis from the behaviour of crossdressing to the inner experience a person had of their sex. In 1913 he coined the term sexo-aesthetic inversion to explain the phenomenon, following this up in 1920 with the introduction of the term eonism to describe people who adopted the role of someone of the opposite sex, in distinction to transvestites who dressed in the clothes of the opposite sex.

A quick side note here, eonism is named after Chevalier d’Éon, a French diplomat and spy, born in 1728. D’Éon lived as a man for 49 years, although he also successfully infiltrated the court of Empress Elizabeth of Russia by posing as a woman.

Despite the theories and work of Hirschfield and Ellis, the distinctions between transsexuality and homosexuality were not broadly accepted until decades later. In fact, the term transsexual itself did not come into use until 1949 when American sexologist, David Oliver Caudwell, introduced it in his essay Psychopathia Transexualis. Caudwell distinguished between biological sex and “psychological sex”. He saw the latter as determined by social conditioning and denied that there were modes of thinking intrinsically linked to male or female biology. It’s worth noting that Caudwell, however, was not in favour of medical transition and, instead, believed that it was better treated as a mental disorder, mainly due to the limitations of medical science but also as he believed “psychological sex” to be plastic.

In fact, despite SRS (sex reassignment surgery) being performed throughout Europe since the 1920s (the most famous case being that of Lily Elbe, whose story was fictionalised and told in the book The Danish Girl), the concept of transsexualism did not reach the mainstream until the case of George Jorgensen was published in the Journal of the American Medical in 1953. Jorgenson was a US WWII army veteran, who travelled to Denmark in 1952 and underwent SRS, returning to the US as Christine Jorgensen. Jorgensen’s case is significant, not just for bringing transsexualism to the public, but also for the influence it had on those who worked with people who felt an incongruence between their sex and their inner feeling of their sex, so we’re going to spend a bit of time unpicking that. Especially as it’s at this point that we really see the idea that having such feelings may have some somatic cause and the conflation of trans with intersex really taking a hold.

I think, though, we can save that for another day, as this post is already quite long, and I want to make this as bite sized as possible. I’m aware that we haven’t gotten anywhere near the theory of gender identity yet, but that feels apt for this cock and bull story. Besides, Jorgensen’s story brings us to the US, and closer to John Money and his work.

Thanks so much for this, Clair.

One question I have is whether surgery at the Johns Hopkins clinic (and I guess European clinics at the same time) was performed on demand, or on the basis of diagnosis.

I think at the moment trans activism is basically dominated by a libertarian understanding of medical and surgical healthcare interventions – they should be purchasable as and when the consumer chooses. But some of the things I’ve read about Johns Hopkins suggest that they performed vaginoplasty not on the basis of patient desire, but on the basis of psychiatrist prescription (which would mean that some people who went to the clinic wanting vaginoplasty would have been refused it, and some people who went to seek treatment for gender dysphoria would have had surgery performed if the psychiatrists treating that person thought it was the appropriate treatment for their condition, even if the individual in question did not want surgery.

I’m possibly prejudiced in this perception because I’ve worked as a psychiatric nurse, and the rest of psychiatry in the mid-twentieth century practised psycho-surgery of the basis of doctor-knows-best, not on the basis of what patients explicitly wanted or sought.

If this is way off where your next installment is heading, I don’t want to distract you from your research. I just suspect that this is one of the areas in which it’s difficult to apply contemporary understanding to the past – ideas of consent and self-knowledge and “the patient knows themself best” were really foreign to even as recently as forty years ago. Actually psychiatry is still rife with paternalism, but it seems (observing from the outside, in Australia) that the gender clinics have separated themselves off completely from psychiatric services, and have embraced, as I described it above, a very libertarian philosophy of healthcare.

Golly, this has turned into a ramble! (It’s my first day of holidays – delicious!!!)

thanks again for your research and blogging,

Seren

I am going to touch on this a bit in the next installment as surgical interventions were by no means an agreed, acceptible practice among medics at this point. The way I see it at the moment, although this may change as I write, some doctors were as keen to justify what they were doing as the patients were desperate for answers and relief. This is why so much reasoning is circular. The science became self-fulfilling for all involved.

Thanks, Clair. Look forward to it.

Eonism is what the trannies call ‘subjective sex’. Serano has pushed this idea as well as ‘female embodiment fantasies’ which is a rebranding of autogynephilia.

Also see Stoller invoking the power of woo in 1964’s ‘A contribution to the study of gender identity’:

‘There are 3 influences on gender identity: anatomy of the genitals, relationship of child to parents, and “a congenital, perhaps inherited biological force“‘

I think Stoller will come up in a future installment. He was part of the wave of the American wave of psychiatrists and sexologists who helped to make this all mainstream with their huge leaps in magical thinking, from what I can tell.

I’m wondering that the huge leaps in magical thinking were made because post-Hirschfeld there was no connection made between boners and trans behaviour. It took Blanchard to make that leap to connect a man claiming to ‘feel like a woman’ to him confusing this with ‘feeling sexy’. It’s like that long lost piece of the jigsaw.

I feel like Harry Benjamin sort of knew this but was too busy being blinded by Jorgensen, “being kind” and making a name for himself. I don’t want to go into that too much here though, as it’s what I’m writing about for Part II.